Well building in Tanzania

August 9, 2009

When’s the last time you marveled at the ease with which you were able to obtain water? For many of us here in the United States, we simply move a lever and clean water instantly rushes from a tap. The water, chlorinated and fluoridated, comes from municipal water systems, quality controlled to meet Department of Health safety standards, or it comes from private wells, pumped from the ground below our very homes. We can choose our preferred temperatures, from skin-scalding hot to ice cubes dispensed from freezers. It’s all too effortless to genuinely appreciate. Filling your glass with water hardly takes more thought than filling your lungs with air. Maybe that explains why, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, the average per-person home water use breaks down to a mind inundating 88 gallons per day. But it’s not so simple for many people elsewhere in our world.

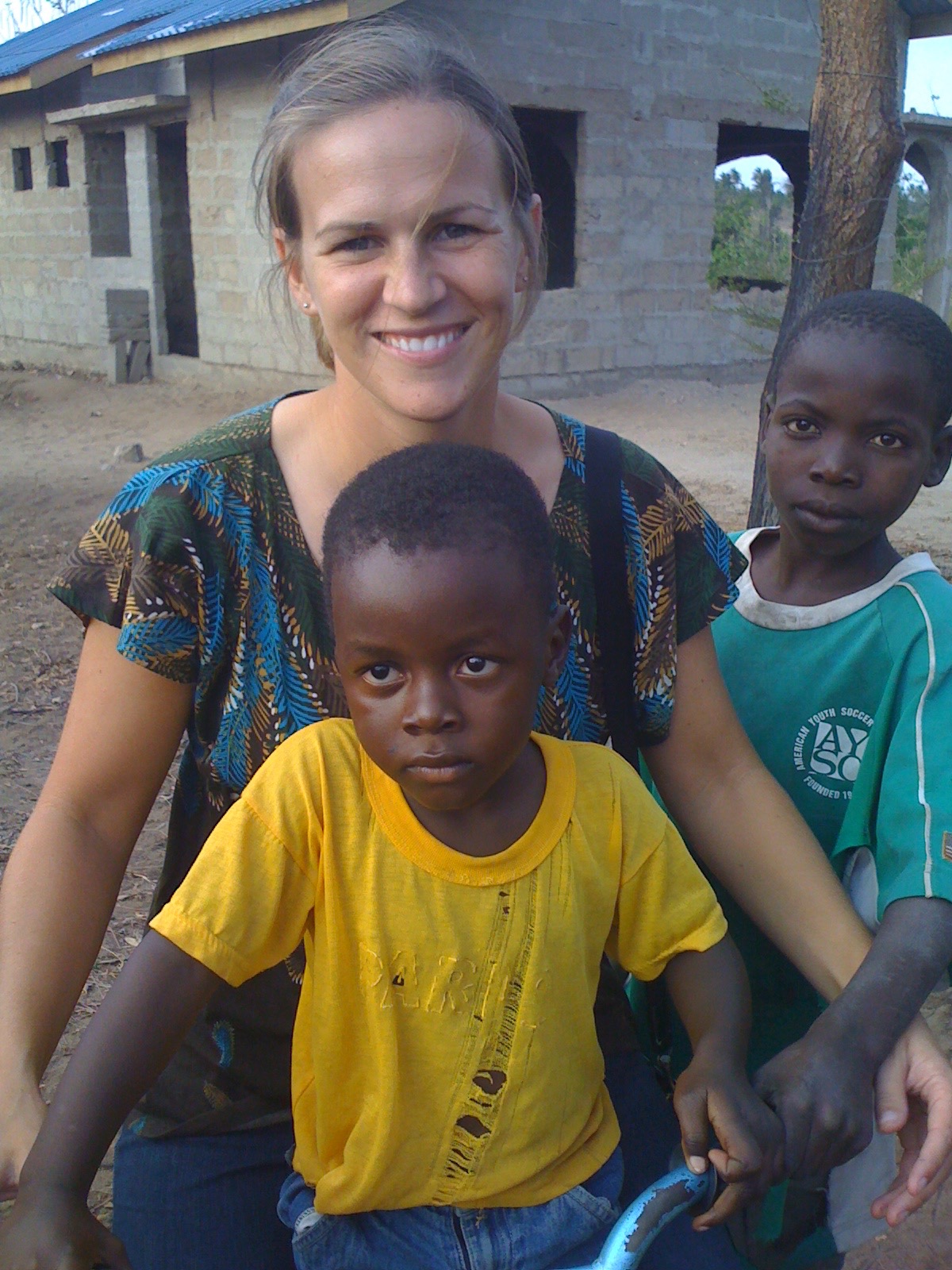

Take our friends in Madala, for example. When we began hosting soccer clinics after school at Wiliam’s house, kids worked up a thirst playing on parched earth under the relentless African sun. When they wanted water, there were no drinking fountains, sinks, or hoses for the kids to drink from. Their only option, in fact, was a hole dug in the ground near the edge of William’s property. There the water table was high enough to produce a brown puddle from which kids, their families, and livestock all sourced their water. The children took turns extending a long stick with an empty oil can fastened to its end into the murky water. Dipping, filling, and retrieving it, they would then transfer the water into an empty one-use water bottle and pass it around for everyone to get a drink, the last person always dumping the remaining couple of ounces in which the visible silt had settled.

Needless to say this was unhygienic. The water, begrimed with dirt, bacteria, and who knows what else, would suffice to temporarily rehydrate, but it also came infused with risky contaminants that are some of the leading causes of death. Indeed, water such as this can transmit diseases like diarrhea, cholera, dysentery, typhoid, and polio. Sadly, it is unsurprising that contaminated drinking water is estimated by the World Health Organization to cause somewhere around 829,000 diarrheal deaths each year. It’s worth reiterating: that’s just diarrhea. When it’s so difficult to get water, you can imagine why hygienic practices like hand-washing become too difficult to practice.

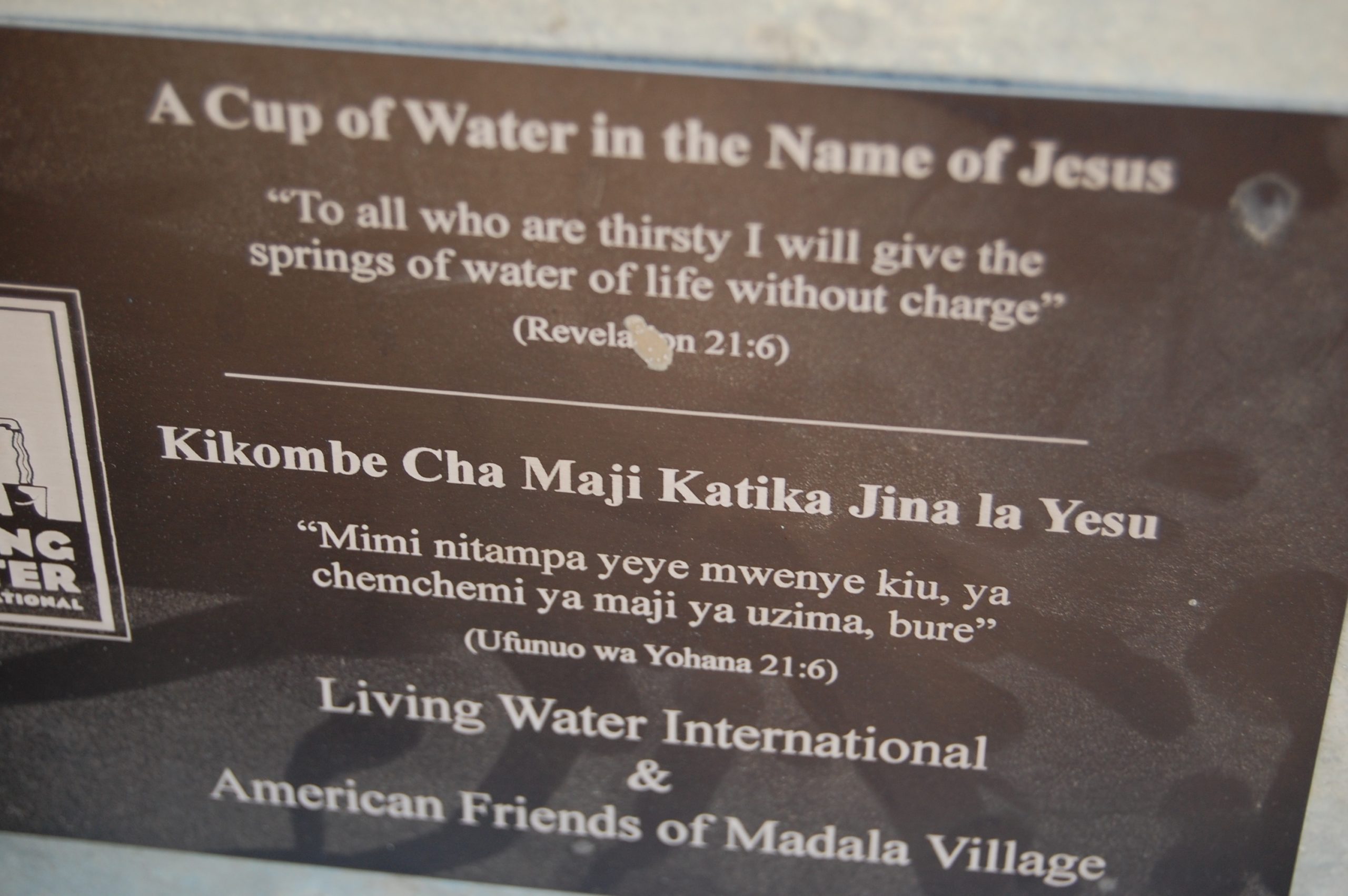

Access to clean water is something we all need and deserve, and our friends and family all knew this to be true. That’s why when we shared the story of the circumstances faced by our friends in Madala, our wonderful friends stepped up to help raise money to build a well. After a few months of fundraising, the goal was met, and we were able to begin construction. This was not to be an easy task. For one, there was the road – or the absence of it. You will recall (from this previous blog) that the treacherous path was a death trap for anything that relied on wheels. It does not require all that much creativity to imagine what could go wrong when we tried to get a drill back to the site. I think the following picture tells the story well:

It took hours, shifts of people, scores of hand-filled sandbags, and a bustling crowd of about seven hundred gawkers to get the truck with its drill back to the site of the well.

Our troubles were not through. The first hole bored led to water, but the salinization levels were too high, so the water wasn’t potable, and the pipes, we were informed, would quickly rust. The decision of whether or not to attempt another well next to the first led to a lot of anxiety. There was no knowing whether the second hole would lead to better water, but in the end, we decided the reward necessitated the risk, and they punched another, much deeper hole. As they say in Swahili, Bwana asifiwe! (Praise God!) They were successful. Kids and families celebrated through dance, song, and prayer as a rush of water gushed up from the hole.

I wish I could say that this was the end of the problems. Not long after, however, disaster struck. Lance, the engineer who came from the United States overseeing the installation of the pipes as they were being connected in sections and lowered by a tripod, winch, and pulley system down the shaft had his hand on the cable when the winch malfunctioned, forcing his hand back into the pulley. Amazingly, not only was he able to remain conscious throughout what must have been a shockingly painful ordeal, but he was even able to direct people on how to remove the thousands of pounds of tension that were on the cable, a step critical for him to free his hand. Additionally, we were blessed to have the Halversons there as well. Kara, who was a nurse, was able to provide immediate care while John drove to the hospital. Without their knowledge, fast response, and vehicle and without Lance’s astonishing composure, the results would have almost certainly been much worse. After multiple surgeries, they was able save part of his hand. His courage, self-effacement, and heart remain an inspiration to everyone in Madala and beyond.

It’s hard to take water for granted in Madala. Everyone but the youngest children remember what life was like without a community well. Even with the well, there are jerrycans to fill and haul. It will be a long time before any one of our friends there fall into such a state of ingratitude as we suffer from due to our being able to take for granted such easy and reliable access to a resource as vital as water. The benefits of access to potable water are clear. Our friends in Madala have experienced better health, increased productivity, and a level of pride that no human should live without. Thank you to all who have helped make this possible. (14 years later the well is still providing water to the community, but has recently been updated to an electric pump with a large reserve tank.

you said: